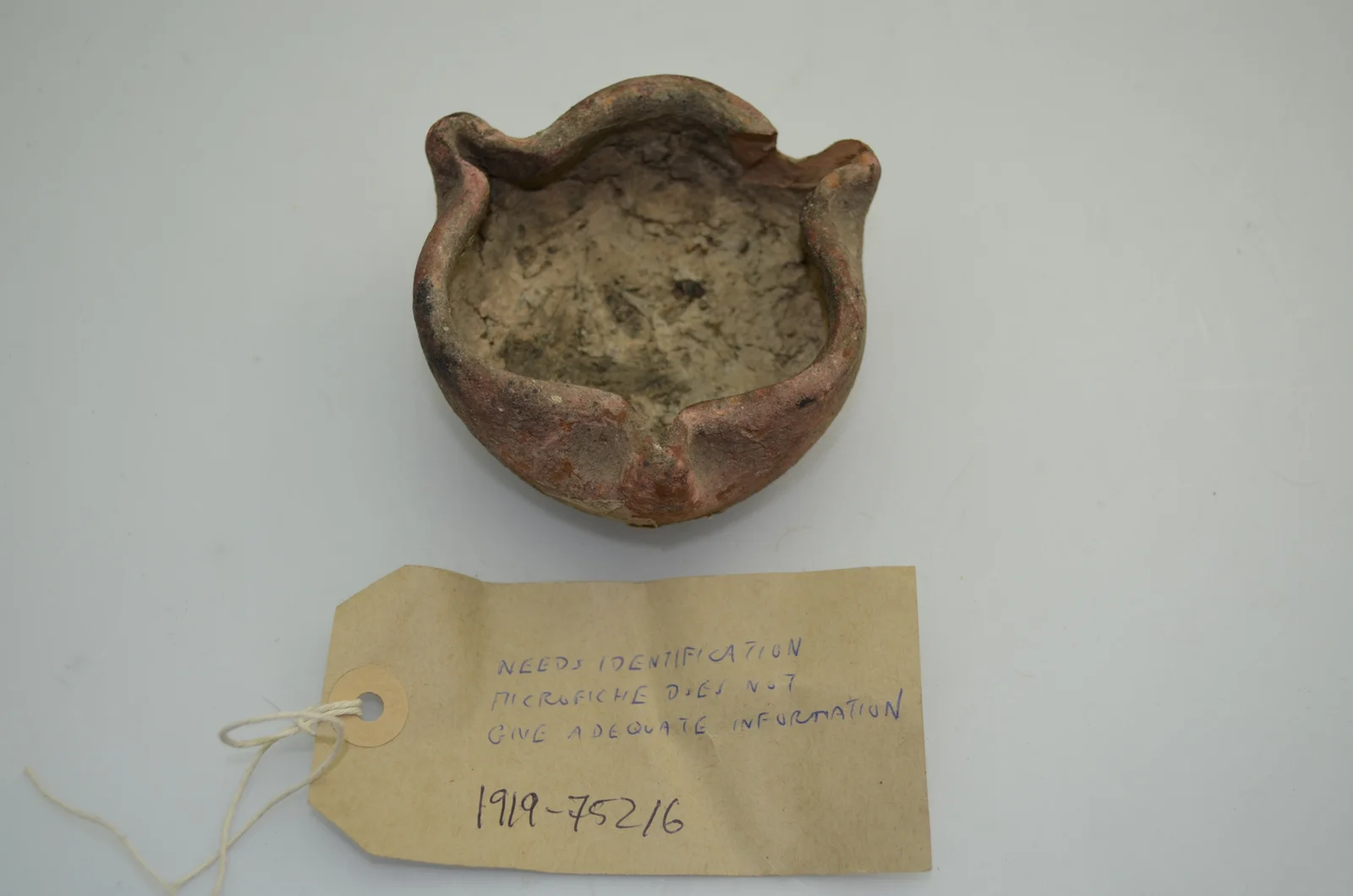

The oil lamp is small and fragile, worn down by almost two thousand years of accumulated grit, corrosion, darkness, and time. It was shaped by hand, with unfired clay, by a refugee fleeing Roman persecution in the fledgling age of Christianity. Its surface is dark with the grime of the underground tunnels where it once illuminated secret pathways. It is an avatar of safe passage in troubled times.

And here, in a museum in Derby, England, a Syrian refugee holds the lamp gently between her hands. She has come across the turbulent sea, with her children, seeking protection and safety. She has fled persecution and violence and horror. She has survived. Her children now play among the objects in the gallery beyond. We can hear their laughter echoing back to us along the corridor. After such a long journey and the endless trauma of their odyssey, they are beginning to find their way in this new country.

She cradles the oil lamp and wonders at its simple power. “It takes you back to ancient times,” she says, “a transportation.” The lamp connects her with her own history, her own journey. It is a companion traveller: fragile and yet resilient. She has come to the museum as a volunteer, to participate in a small community project focused on teaching participants how to clean ancient objects. She’s not in therapy, and her experiences here have not been facilitated as traditional psychotherapeutic activities. The museum staff emphasize connection, belonging, and wellbeing — foundations for any counselling or therapeutic initiative — but cultivate these in ways not commonly seen in counselling practice. There’s less formality here, fewer signs of explicit mental health promotion, more social connection and fluidity. Over the past several years I’ve participated in a number of projects like this, and each time I’ve been struck by the ease with which psychotherapeutic themes emerge, by the fluent and organic ways in which people find their paths of healing. And I am consistently reminded, in this work, of the primacy of the objects: their weight of symbols and of stories, the curious and often synchronistic manner of their involvement with participants. In this context of object interactions in cultural institutions, it is the objects themselves that drive the therapeutic process.

In the deepest recess of the bowl of the oil lamp, in a whorl of dried clay, the Syrian refugee has found the thumbprint of the maker. Ancient and persistent, that thumbprint, as though it calls across time with messages of succour and solace. Messages of flickering light across a vast and shadowed sea. As her children chase one another around a display of culinary tools from Mesopotamia, as autumnal light splays across the gallery, as she thinks about her journeying and arrival, the lamp becomes a marker and a talisman. The lamp affirms her path, encourages her, shares with her a personal example — ancient and yet present — of the universal human struggle to heal. The thumbprint carries her toward a feeling of unity, of identification with that distant maker who crafted this light from the dark earth. In resonance and recognition, she pauses, smiles, then says “I feel rapture over everything! With the oil lamp I feel like I could almost be making it.”

The museum gallery has a collection of ancient oil lamps, from far-flung times and places, as well as many other cultural objects: suits of armour, masks, jewelry, sculptures, weapons, bowls, clothing, and an array of objects of uncertain or unknown origin. An avalanche of accumulated time, of creativity, of humans roaming the landscape together. I’ve had dozens of conversations here with participants keen to share their reflections and impressions of their chosen or favourite objects: a camera, a flag, an amulet, a totem, a statue, a bracelet, and many more. In each of these conversations I’ve heard stories about trauma and healing, loneliness and connection, damage and growth. The objects open pathways — surprising, powerful, compelling pathways — which participants follow into themselves. The objects facilitate reflection and discovery, they broaden and solidify the community. These experiences are some of the deepest therapeutic work I’ve seen: organic and playful, yet at the same time rich with depth and meaning. Almost everyone I’ve worked with here shares, with their own objects, the perspective of the Syrian refugee when she says, of her interactions with the lamp: “it illuminates me — my mind, heart, creativity.”

It’s wonderfully engaging and affirming for me to participate in these projects. And humbling, too: the object interactions are much more impactful than anything I could design as a therapeutic strategy. In museum settings I focus on ensuring that participants are safe, that they do not exceed their emotional capacities, and I routinely use my skills as a trauma specialist to manage situations of overwhelm, dissociation, or freezing. Such moments do happen in this work, as in any work of deep engagement. But I am also aware that my role here is somewhat different than what I am used to: I’m not the guide or the catalyst for the work that participants do. Indeed, it is the objects which fulfill that role, in ways that can be opaque and seemingly alchemical. Participants often speak of the objects as though they have agency. It’s easy to share that view, especially when I hear participants repeatedly speak of objects as having saved their lives or enabled them to heal. For participants, the objects possess their own authentic power. Emotional power certainly, and often spiritual power as well. The healing that takes place begins with the object, not with a psychotherapeutic invitation. It’s strange, and yet very rewarding, for me to take a secondary role in what is so obviously a profound experience of healing for so many people. It makes me think about who is the therapist, and what therapy means.

The oil lamp. Made about 200—650CE, found in the early Christian catacombs of St Agata, Rabat, Malta, in 1918. Courtesy of the Derby Museums Trust.

At the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, at the War Childhood Museum, at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) Museum in New York, and here at the Derby Museum in the UK: in all of these projects, participants have utilized museum objects in ways that can only be described as therapeutic. Survivors of 9/11 have used keycards, watches, clothing, and a multitude of personal objects to help facilitate their recovery from trauma. Participants who were children during wartime in Bosnia have found meaning in toys, bicycles, food wrappers, fragments of bomb-blasted masonry, and many stark objects of war. Participants in the FIT project have drawn inspiration from the intimate and infinite ways in which clothing intersects with our personal lives and our healing. In every case it is the objects which have guided and shaped the healing of the participants. Insights are gleaned from interactions with the objects, honed by way of conversation with mental health professionals, and shared within the community. In turn, the community is enriched and the participants anneal their personal challenges by way of cultural and social bonds.

Utilizing cultural institutions as allies in healing is a growing field of counselling and therapy which has emerged, in part, because of the very complexity of many contemporary challenges. Pressing issues such as climate change, social isolation, terrorism, war, and economic instability cannot be solved through individual efforts alone and therefore lend themselves to initiatives focused on community connection and cultural participation. In the UK, organizations such as The Happy Museum Project are focused explicitly on the relationship between mental health and cultural action. A broad network of such organizations has begun to flourish in the UK and has been instrumental in the movement commonly known as social prescribing, in which health practitioners prescribe cultural and social activities to their patients.

As a result of these innovations, ideas about the nature and process of counselling and therapy are broadening, practitioners are beginning to forge partnerships across disciplines and domains, and cultural institutions are starting to explore new modalities that help us grapple with the always complex and often intractable issues of our age. Here in Canada, cultural institutions have begun to develop wellness programs on the social prescribing model (such as at the Royal Ontario Museum) and to support the work of mental health professionals in museum settings (such as at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts). These projects further extend what is already a worldwide movement of museum professionals and mental health experts working together. The most straightforward form of these collaborations is social prescribing, which typically takes the form of free admission to a museum, or encouragement to participate in a cultural or arts-based activity. In England, social prescribing is now supported by the National Health Service. Similar initiatives have begun to appear in Canada, with pilot projects underway in Ontario and Quebec.

My own work has been focused particularly on museums: first in the United States, then in Europe, and now in Canada, with organizations such as the Canadian Museum of History, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and the Vancouver Art Gallery. Objects in museums tell the stories of who we are and where we came from. Stories are maps, repositories of collected wisdom, ciphers and guides for making sense of the human journey. Whether archaic, prosaic, or postmodern, stories render the paths undertaken by all those who seek resolution and healing. At the 9/11 Museum, a participant — a man with the most harrowing account of survival I have ever heard — told me that “each object tells a different part of the story of that day.” The story coheres and contributes, it grows and changes in the lives of its participants. “The objects make me think of the people that perished,” he said. “This object [an ID card] shows that I got a second chance... I got out alive.”

Working with my colleagues Brenda and Jason, interviewing a participant about the meaning of a personal object.

The connection between objects in the hand and the path of personal healing is profound, often mysterious, and — for me — always surprising. Objects act as allies and guides, as symbols, and sometimes as challenges or rejoinders. Each one is distinct, and the abundant diversity of their interactions with different people yields new and untrodden paths. A museum is a repository of object stories, colliding and interweaving, carrying forward the embodied past, holding the hardscrabble present, shaping the possible future. The diverse tales of objects, of their curious and potent power, contain many similarities and many shared moments of discovery. The map of healing is revealed by these moments, by the lamplight they cast over a landscape of searching and wandering.

The companionship of stories, the crafting of new scenes and chapters, the collecting of hard-won wisdom: these are all aspects of the unfolding story of every human and of humanity itself. Small and often quotidian object stories are fragments of an ever-evolving tale about what it means to grow, learn, and heal as a human. These stories, collected together in museums and cultural institutions, embody that collective and unfathomable human narrative; they share its richness and warmth.